The Cartridge

This an extract from Mike's Book on the History of Clay Pigeon Shooting

Early cartridges—the word comes from the French cartouche — or Italian cartoccio or cartuccia— were no more than charges of powder boxed or wrapped individually to speed up the process of loading. In the latter case, these might be made of paper—hence the modern term cartridge paper—linen or other materials which might also be greased or waxed to improve weather resistance. Leonardo mentions the existence of paper cartridges circa 1500; by 1600, cartridges containing both powder and ball were in widespread use . Typically, a paper cartridge containing powder and ball would be tied at the ball end and folded with a tab at the powder end. The tab was torn or bitten off as loading commenced, a small amount of powder was used to prime the pan, and the remaining powder poured down the barrels followed by the paper tube with ball. The ball was rammed home with the paper body of the cartridge acting as both wad and patch. Ingenious though this was, there was not much that could be done to develop the cartridge while the flintlock system prevailed.

Percussion ignition

The possibilities for break through began in the late eighteenth century with new experimental work on explosives. In 1788, a French chemist, Berthollet, replaced saltpetre in gunpowder with potassium chlorate. The resulting compound was dangerous to make and unpredictable in use. Berthollet abandoned this line of enquiry. Similarly, in 1800, Edward Howard, a member of the Royal Society, published a paper on the preparation of mercuric fulminates.* He had tried the latter substance as a propellent substitute but had blown his laboratory up in the process. “I must confess,” he observed afterwards, “I shall [now] feel more disposed to prosecute other chemical subjects.”

All these efforts were not wasted, however. They led the Scottish cleric and chemist, Alexander Forsyth, M.A., L.L.D, to attempt similar experiments. He had similar problems too, but Forsyth was not a man to give up easily. He began to consider the use of the violently explosive new compounds as detonating agents rather than as propellants. He tried them in the pan of a normal flintlock, but found that they flashed too quickly to ignite the main charge. Eventually, it dawned on him that he might use a hammer blow for ignition instead of the conventional spark. It was a thought which would change the world. In the spring of 1805, Forsyth created an experimental lock using the percussion principle and attached it to a sporting gun which he used for a season’s game shooting. It worked well. Not only was ignition more reliable than with flint and steel, it was much faster, making wingshooting easier.

All these efforts were not wasted, however. They led the Scottish cleric and chemist, Alexander Forsyth, M.A., L.L.D, to attempt similar experiments. He had similar problems too, but Forsyth was not a man to give up easily. He began to consider the use of the violently explosive new compounds as detonating agents rather than as propellants. He tried them in the pan of a normal flintlock, but found that they flashed too quickly to ignite the main charge. Eventually, it dawned on him that he might use a hammer blow for ignition instead of the conventional spark. It was a thought which would change the world. In the spring of 1805, Forsyth created an experimental lock using the percussion principle and attached it to a sporting gun which he used for a season’s game shooting. It worked well. Not only was ignition more reliable than with flint and steel, it was much faster, making wingshooting easier.

Immediately realising both the sporting and military potential, Forsyth set off for London in 1806 to obtain official backing. Lord Moira, the Master General of the Ordnance was sufficiently impressed with the revolutionary lock to arrange for its inventor to be set up in a secret workshop in the Tower of London. Moira wanted the system applied to a strong, waterproof lock, suitable for firearms and cannon. Forsyth worked for almost a year and produced prototypes, but his tenure came to an abrupt end when John Pitt, brother of William, took over as Master General of the Ordance. Evidently, he was not much of a shooting man. Forsyth was ordered out of the Tower forthwith and told to take his “rubbish” with him.

In 1807, the somewhat disillusioned cleric sought patent protection with his friend, James Watt, of the condensing steam engine fame, acting as adviser. The result was British patent 3032 of 1807 which was most carefully worded and which proved to be extremely strong when later challenged at law. It stated:

...instead of giving fire to the charge by a lighted match, or by flint or steel, or by any other matter in a state of actual combustion applied to a priming in an open pan. I do close the touch-hole or vent by means of a plug or sliding piece, or other fit piece of metal...so as to exclude the open air, and to prevent any sensible escape of the blast or explosive gas outwards...as a priming I do make use of some or one of those chemical compounds which are so easily inflammable as to be capable of taking fire and exploding without any actual fire being applied thereto, and merely by a blow, or by any sudden or strong pressure...*

In 1808, Forsyth found backing from a barrister cousin called Brougham - a rather lack-lustre individual by all accounts - and opened a gunshop in Piccadilly with the talented ex-Manton employee James Purdey as his gunsmith. In the years that followed, Forsyth and competing gunmakers (who were continually trying to circumvent his patent) developed a number of improved percussion locks and detonating compounds. Some had a reservoir which dispensed the detonating compound (for example, Forsyth’s famous “scent bottle”), some used paper caps or quills filled with fulminate, others used pills of fulminate or metal tubes filled with the substance. The tubes as developed by Joe Manton were favoured by some wildfowlers because they were the least affected by wet conditions.

It is hard to over emphasise the importance of Forsyth’s invention—it was certainly of no less import than his friend Watt’s famous engine. It allowed for the creation of vastly improved, quicker firing, firearms, reduced the requirement for sustained lead in wingshooting and led directly to the development of the self-contained, central fire cartridge. Few inventions have had more profound consequences for good and ill.

The percussion cap

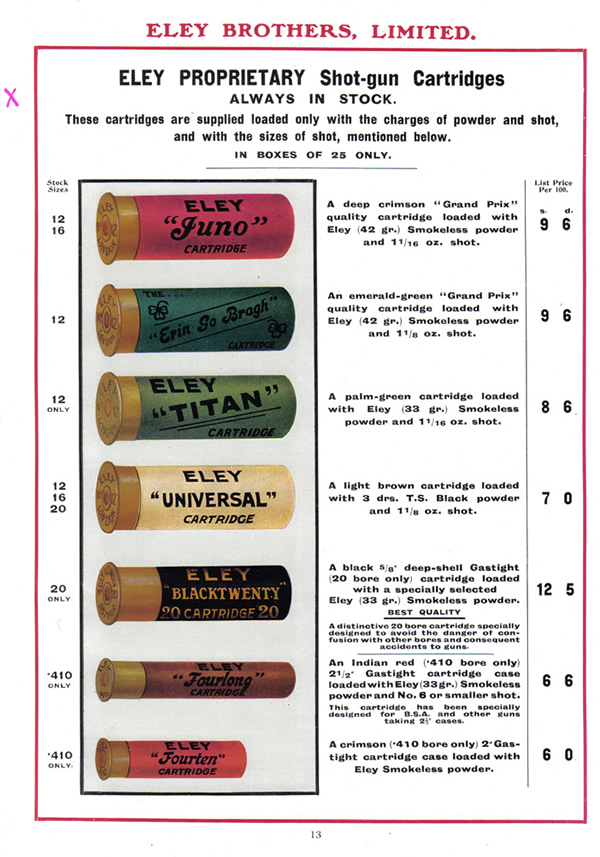

In the second decade of the nineteenth century (there is much argument about the exact date) the metallic percussion cap was introduced. In it, detonating compound was placed in a soft metal cap which could be placed over a nipple at the gun’s breech. It was not Forsyth’s invention (indeed, his patents appear to have held back its introduction), but his work had made it possible.* Percussion cap locks, unlike earlier detonators, were suitable for mass production, but there remained great dangers connected with the bulk preparation of detonating compounds. William Eley, one of the founders of the Eley cartridge making dynasty, perished in an explosion in his factory in Bond Street in 1841 aged 46. To quote Hawker he: “was blown to atoms by an awful explosion of fulminating mercury, from which everyone around him escaped with, comparatively, little injury” and his sons carried on the business - so Eley Bros. was formed”.

A every schoolboy used to know, the greasing of paper cartridges was one of the causes of the Indian Mutiny: Moslem troops believed that pork fat had been used and the Hindus, beef.

*Fulminates of mercury, silver and gold had been known for many years. Samuel Pepys mentions fulminate of gold and its explosive properties in his famous diary. According to Howard Blakemore, the first man credited with making fulminate of mercury was a German Alchemist by the name of Johann Kunckel (1630-1703). However, it was not until the late eighteenth century that reasonably safe methods of manufacture were developed.

* By this time, Forsyth had been experimenting with a variety of detonating compounds, including potassium chlorate, which the French had also been considering as a replacement for gunpowder.

* The invention of the percussion cap has been claimed by Colonel Peter Hawker, Joe Manton, Joseph Egg, Joshua Shaw and a number of others. Shaw, an English gunsmith who emigrated, is generally credited with the invention today. He claimed to have made a cap from iron sheet in 1814 and pewter and copper examples by 1816. Noting that there would have been a difficulty taking out a patent in England because of Forsyth’s comprehensive patent protection, he first patented his invention in the U.S.A. in June, 1822. Nine years later, he wrote, “I have been in the habit of using copper caps for at least 13 years and for the past seven years have manufactured and sold them at the rate of two million annually.”